Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799) was born into one of the most contradictory eras of modern European history. On the one hand, the valorous ideals of the Enlightenment caught fire during Bologne’s lifetime, as Enlightenment thinkers such as Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) called for the individual to pursue knowledge and to expand their worldviews. On the other, the horrifying principles of scientific racism, coupled with the booming market of the transatlantic slave trade, unleashed violence upon the Atlantic world in a manner that remains unprecedented. Joseph Bologne arrived into the world when, as Henry Louis Gates Jr. writes, “Enlightenment-era thinkers made use of the rhetoric of progress and humanitarianism in order to rationalize human bondage.”

Many may think that they are familiar with the history of slavery and the Black diaspora—how white colonists enslaved millions of indigenous West Africans and forced them to work in the New World on plantations harvesting sugar, tobacco, and other products for export. But the fact of the matter is that people of African descent lived and died on European soil as well. As the French historian Robin Mitchell writes, “Europeans went to considerable lengths to disguise the extent to which buying and selling human beings was a lucrative enterprise.” While the rhetoric that Europe “had no slaves” may exist, many European regimes depended on slavery in the colonies—as well as at home. Black lives in Europe have historically been erased from the moment they made their existences known on European soil. For far too many people, Black Europeans, past and present, are an odd anomaly that never should have existed.

Many may think that they are familiar with the history of slavery and the Black diaspora—how white colonists enslaved millions of indigenous West Africans and forced them to work in the New World on plantations harvesting sugar, tobacco, and other products for export. But the fact of the matter is that people of African descent lived and died on European soil as well. As the French historian Robin Mitchell writes, “Europeans went to considerable lengths to disguise the extent to which buying and selling human beings was a lucrative enterprise.” While the rhetoric that Europe “had no slaves” may exist, many European regimes depended on slavery in the colonies—as well as at home. Black lives in Europe have historically been erased from the moment they made their existences known on European soil. For far too many people, Black Europeans, past and present, are an odd anomaly that never should have existed.

In fact, one of the greatest mythologies or even fallacies that still floats around like a miasma is that Europe has no Black diasporic history of its own, a line of thinking that should be vigorously interrogated at every turn. For decades, Black Europeans have been calling for the teaching of Black European history in schools and across public platforms. “We Euro-Africans still lack our own positive, inspiring symbols and leaders, our Martin Luther Kings, our Rosa Parkses, our Barack Obamas,” the Black Italian journalist Vittorio Longhi writes. Because of the lack of public history on Black Europeans, the idea that someone can be Black and European has often been contested or presented as a contradiction—when not met with outright derision. “Striving to be both European and black,” the Black British writer Paul Gilroy once observed, “requires some forms of double consciousness.”

Joseph Bologne, however, represents a Black European historical figure whose biography overturns these contradictions, even while he was born in the decades of their formation. A talented violinist, conductor, and composer, Bologne was able to navigate Europe’s changing social landscape through sheer force of will. He was born in the French Caribbean colony of Guadeloupe to a white French plantation owner Guillaume Bologne de Saint-Georges and a young enslaved African woman named Nanon. His father, Guillaume, acknowledged his son at birth, granting Joseph his surname and the protections that came with it. At age seven, Joseph traveled with his parents to France, where he lived until his death.

When Joseph first landed in Bordeaux as a child, he stepped into a turbulent world where the rights and status of Black people were in extreme flux. Black population numbers changed from region to region, always monitored by varying regimes. In the Mediterranean world—geographically closer to Africa and featuring port cities that were crucial to the slave trade—cities such as Lisbon were so mixed that one tourist described it as a “chess board,” with as many Black as white people wandering around. In England, the Black population numbered in the tens of thousands, accounting for almost 3% of the population of London alone, whereas the German-speaking lands numbered more in the hundreds. In France in 1777, roughly three thousand people out of a population of more than twenty-five million were of African descent.

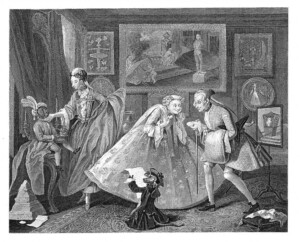

The murky social status of Black people in Europe makes their stories all the more complicated and occasionally heartbreaking, for they occupied a range of positions, from enslaved person to domestic servant to nobility themselves. Between 1700 and 1780 alone, over eight hundred posts appeared in British newspapers calling for the return of runaway slaves. Yet others across Europe lay somewhere between enslaved and free. As the historian Vera Lind has observed, many Black figures had a status of “privileged dependency,” being dependent on the generosity of the noble families who housed them. Many Black people in Europe had been kidnapped as small children and given as exotic “gifts” to European aristocrats, presented in the same manner as one would offer up a tiger cub. In fact, the custom of giving a small Black child to an elite family in Europe was so popular that the British artist William Hogarth satirized it in his painting Taste in High Life (1742). In the work, two white British ladies and a gentleman are dressed in the latest styles imported from France, and one of the women is tickling a small Black child under the chin as if he were her pet.

In this ever-changing social climate, both upward and downward social mobility in continental Europe was possible. Anton Wilhelm Amo (1703-1759) was born in present-day Ghana and brought as a child to Wolfenbüttel in Germany, where the duke supported his intellectual talents and provided him with an education at a young age. Amo earned a PhD in Philosophy from the University of Halle in 1729, most likely becoming the first Black person to have a PhD from a European university. Others, however, did not share the same fate, being passed around from house to house, suffering abuse, violence, or even death at the hands of their supposedly magnanimous white ‘masters.’ Other cases, such as Angelo Soliman (1721-1796), are trickier still. Abducted from present-day Nigeria as a child and eventually gifted as a present to an Austrian prince, he became the top servant of the Habsburg empire, married a noblewoman, and eventually became Grand Master of a masonic lodge whose members included Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Joseph Haydn—only to be stuffed and placed on display in the Habsburg palace as a museum curiosity upon his death, standing in the same halls he had once served when he was alive. Even Anton Wilhelm Amo, it should be noted, suffered racist threats and violence in spite of his education. By the end of his life, having grown bitter, disillusioned, and fed up with the racism he had endured, Amo purchased a one-way voyage to Ghana, where he died.

Ultimately, the numbers of Black Europeans in the 18th century, however small or large, were always rigorously policed—to which Bologne’s own biography can attest. No better example of European attempts to limit their Black populations exists than the Code Noir, first established in 1685 and altered significantly by the time Chevalier de Saint-Georges was born. A royal decree intended to limit sexual interactions between Black and white people in the colonies, the law soon came to be extended onto French soil as well. By 1738, marriages between Black and white people in France were forbidden. By 1777, France had created a “Police des Noirs” (police for black people) and made it compulsory for Black people to carry an identification card.

The status of children born of these interracial relationships also shifted in Joseph Bologne’s lifetime. These children “blurred those racial lines that had been established by the anatomists,” historian Olivette Otele writes, and “as a result, it was felt that they had to be carefully monitored.” Tension mounted between white French men from the colonies who wished to be in France with their biracial children and claim them as legitimate, and white French society that did not want to see them on the streets of Paris or Nantes.

Black musicians such as Bologne delicately navigated these racist obstacles and barriers that were hardening in place. Their biographies are testaments to their unabashed rejection of two important trends in the 18th century: first, the growing fixture on race as a permanent and negative marker of one’s (in)humanity and second, the increasingly close tie between Blackness and labor or status. The life of Black Italian opera singer Vittoria Tesi Tramontini (1701-1775), for example, illustrates how Black Europeans could slip through these hardening social cracks. The daughter of an African servant and a Florentine woman, Vittoria Tesi became one of the most important opera singers of the 18th century, performing in Dresden, Naples, and Venice before settling in Vienna in the 1740s. She sang operas composed for her by Christoph Willibald Gluck and others, was great friends with the famous castrato singer Farinelli (1705-1782), taught the next generation of opera singers, and died fabulously wealthy in a palace in Vienna. George Bridgetower (1778-1860), the son of a Black Caribbean servant at the famous Esterházy noble family and a white Polish woman, also illustrates how the path of musical performance could rescue Black Europeans from a life of servitude. At a young age, Bridgetower was gifted in violin, and at the age of ten moved to London to continue his training.

Joseph Bologne, then, is both exceptional and unexceptional within the world of Black Europe. Like Vittoria Tesi Tramontini and George Bridgetower, Bologne was one of those children that white European societies stated they did not wish to see on their streets. To some, he was an example of the dangers of racial mixing, having risen above his racial “status.” With the support of his aristocratic father, Bologne received a nobleman’s education and became one of the most accomplished young men in the French empire, mastering fencing, equestrian sports, and, of course, musical composition. Nonetheless, as the son of nobility, Bologne had difficulties finding a wife who would agree to marry him, even though he was reported to be handsome and popular.

It is understandable, then, why Joseph Bologne would be attracted to the spirit of the French Revolution when it broke out in 1789, for its promises to dismantle the aristocracy and create a just and equal society must have sung out to his heart. In Paris, he made it his mission to find people of African descent who wished to join the same cause, including Thomas Retoré Dumas, later to be the father of Alexandre Dumas (author of The Three Musketeers). Envisioning a Black French army of sorts, Bologne served as a leader in the French Revolutionary Army for years. Joseph Bologne dedicated his efforts toward ridding Europe of its racist present and finally embracing the Enlightenment ideals it claimed to espouse. The racist contradictions that guided European societies, Bologne avowed, would have no business determining his life.

By: Kira Thurman

Kira Thurman, Ph.D. is a professor of History, Musicology, and German Studies at University of Michigan who specializes in the relationship between music and national identity, and Central Europe’s historical and contemporary relationship with the Black diaspora.