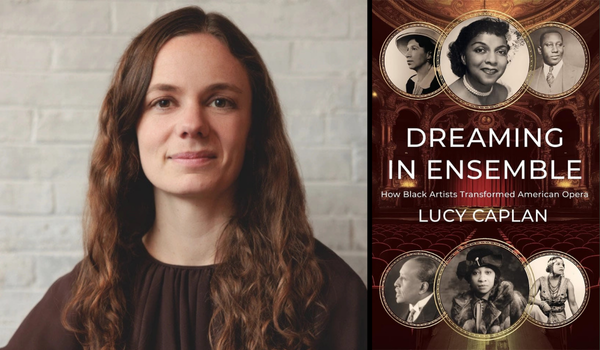

By Lucy Caplan

On July 22, 1933, thousands of people streamed into Manhattan’s Hippodrome Theater, undaunted by sweltering temperatures and teeming crowds, eager to witness a performance of Aida unlike anything they had seen before. The 5,300-seat theater, the largest in New York, had sold out days in advance, and patrons clambered for standing-room-only spots; still more were turned away at the door. Many in the audience were Italian American, and about one-third were African American. The evening’s star, soprano Caterina Jarboro, entered to prolonged applause. Fanning their programs in the heat, the audience greeted her with what one critic called a “tremendous ovation” as “Italians sat in admiration. White America gasped in amazement. And Harlem applauded its heroine in magnificent and splendorous debut.” By evening’s end, Jarboro had become the first African American woman to appear in Aida with a previously all-white opera company in the United States.

This was a momentous occasion. It marked a turning point in Black operatic history, allowing Jarboro to generate new, potentially liberatory meanings from the canonical role of Aida. Years after Jarboro’s debut, the inimitable Leontyne Price reflected, “When I performed Aida, the color of my skin became my costume, and that gave me an incredible freedom no other role could provide.” To Price, Aida was a role brimming with possibility, rooted in the shared identity of performer and character and culminating in nothing less than the attainment of freedom. “This very minute,” Price elaborated, “Aida says things about where I am as a woman and as a human being, about my life and the progress, or lack of, of millions of people at home in the States—things I could not have said as eloquently in other ways.” Her layered claims about race, gender, and citizenship insist on Aida’s interpretive richness and political salience, wresting the opera into the urgency of “this very minute.” The musicologist Naomi André affirms this sensibility in a meditation on Price’s performance of the aria “O patria mia,” in which Aida yearns for her Ethiopian homeland: “I feel how real these words are: ‘Oh my country, how much you have cost me.’ It feels like a moment when the drama onstage and the reality offstage crash together . . . Revealed in this voice is the childhood in Mississippi during the 1930s and 1940s; the proud and puzzled receptions of her operatic singing by her family, community, and audiences around the world; the comments she must have endured.” Both Price’s and Jarboro’s performances were part of a genre-spanning phenomenon in which, as the literary scholar Farah Jasmine Griffin writes, the Black woman’s voice “is like a hinge, a place where things can both come together and break apart.” Both the role and the celebrity status that it afforded to its performers promised to forge new ways of understanding the relationship between the European operatic past and the African American present.

Aida originated when the Egyptian khedive, Isma’il Pasha, commissioned Giuseppe Verdi and librettist Antonio Ghislanzoni to write an opera on an Egyptian subject; having never visited Egypt, they drew heavily on the work of French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette. (Or, as Naomi André pointedly describes it, “Aida is a made-up story by Italians and Frenchmen set in the time of the Pharaohs with little knowledge of the historical Egyptians and Ethiopians and makes no reference to living Egyptians or Ethiopians during the late nineteenth century.”) The opera premiered in Cairo on Christmas Eve, 1871 and was performed for the first time in the United States at the New York Academy of Music in 1873. Most productions portray its Egyptian characters as white (or racially unmarked) and Ethiopians as Black, a convention that dates to an early production book indicating that the Ethiopian characters have “olive, dark reddish skin.” As a result, white singers often have performed the role of Aida (as well as that of her father, the Ethiopian king Amonasro) using skin-darkening makeup. This practice persisted throughout the twentieth century and continues to this day.

If Aida looked backward to both the imperialist and exoticist tendencies of nineteenth-century European grand opera and the American tradition of blackface performance, African American artists looked forward, identifying the opera as a touchstone for creative engagement with the European canon. As early as the 1890s, the star soprano Sissieretta Jones was praised as “like a veritable Aida”; one critic wrote that “the thought was irresistible that she would make a superb Aida, whom her appearance, as well as her voice, suggested.” The Theodore Drury Grand Opera Company, an all-Black opera company founded in New York City in 1900, offered the first fully staged productions of Aida by African American singers in 1903 and 1906; both featured soprano Estelle Pinckney Clough in the title role. Black concert singers frequently included arias from Aida on recital programs—including Roland Hayes, who often began his recitals with “Celeste Aida.” Across the country, African American musical clubs were named in her honor: the Aida Club of Musical Art, the Aida Choral Society, the Aida Choral Club. In 1927, in the southern Italian city of Cosenza, the Detroit-born soprano Florence Cole-Talbert became the first Black woman to sing Aida with a European company. The Italian press noted that she was able to sing the role “excellently without darkening her skin,” while the New York Amsterdam News rejoiced, “The critics need no longer complain that Verdi made his greatest heroine black, forcing white singers to make themselves up for the role . . . we have our own Aida.” Jarboro’s American debut in the role came six years later.

Opera Singer Madame Florence Cole Talbert, 1925

The woman who would become Caterina Jarboro was born Katherine Yarborough in Wilmington, North Carolina in July 1898. Her father, John Wesley Yarborough, was a barber, an occupation that afforded the family a comfortable position in Wilmington’s Black middle class. He and his wife, Elizabeth, planned to raise Katherine and five siblings in a picturesque Queen Anne cottage east of the Cape Fear River. The relative stability of their life, however, was shattered just months after Katherine’s birth, in November 1898. A white supremacist mob staged a political coup and murdered dozens of African Americans in the now-infamous Wilmington Massacre, marking the beginning of a tyrannical period in which terroristic violence and economic and civic disenfranchisement threatened local Black citizens’ lives. This fundamental social reordering may well have shaped Jarboro’s decision to leave the city at an early age, moving to New York as a teenager to live with an aunt. By 1921 she had joined the cast of the wildly successful Broadway show Shuffle Along, and in 1926 she moved to Europe to study opera. She followed the example of Cole-Talbert, making her debut as Aida at Milan’s Puccini Theater in 1931.

Caterina Jarboro in costume

Photographed by White Studio

Upon returning to New York in 1932, Jarboro met the impresario Alfredo Salmaggi, who engaged her to sing Aida. An immigrant from central Italy, Salmaggi was a larger-than-life figure whose Chicago Grand Opera Company produced “popular price opera,” massive and extravagant productions for which tickets cost less than a dollar. Known by sobriquets like “the P. T. Barnum of bargain opera” and “the greatest producer of second-rate opera in the US,” he favored spectacle and excess: parades of animals, enormous choruses, and a generally circus-like atmosphere. For him, hiring a Black singer to perform the role of Aida may have been a way to heighten the production’s spectacular nature and appeal to his audience’s taste for novelty rather than an entirely new or antiracist endeavor. (Indeed, in 1936, Salmaggi engaged the boxer Jack Johnson to play a [silent] Ethiopian general in Aida, clad in an outrageously primitivist leopard- and zebra-print costume.) Despite these limitations, though, Jarboro embraced the opportunity. The circumstances of her debut suggest that her glamorous self-construction had a transgressive edge: her insistence on personal independence enabled her to push back against the spectacularizing constraints of the stages on which she appeared.

Photographed in costume, Jarboro radiates glamour. Adorned in necklaces and bracelets, a jeweled ankle-length dress, and a headband dripping with beads, she gazes into the distance with determination and confidence. Her great-nephew, the literary scholar Richard Yarborough, recalls that his great-aunt had a commanding presence, and that “how she carried herself physically was not stereotypically feminine.” Instead, her affect was “regal, with her taking for granted that she was the center of attention. She could be raucously funny, but she didn’t joke about her celebrity, which she saw as fully deserved.” That same self-possession emanates from this photograph, marking another way Jarboro might have used her embodied presence to contest the histrionic aesthetics of the Salmaggi production. Her Aida was not solely the feminized object of Radames’s romantic love and Amonasro’s paternal love, but also a character confident in her own dignity.

Jarboro’s singing was never recorded, but contemporaneous and retrospective accounts give some indication of its character. At her New York debut, one critic wrote that her voice had “the range of a mountain and the clearness of a bell,” a poetic description suggesting both technical excellence and authoritative presence. Both qualities would have been exceptionally impressive in the cavernous Hippodrome Theater, where Jarboro had to make herself heard above the choristers and animals crowding the stage. That same charisma and authority can be heard in an interview Jarboro gave in 1972. She rarely answers the interviewer’s questions directly, instead telling whatever stories she prefers to tell. Although past her vocal prime, she evokes her operatic abilities, tapping her microphone and telling the interviewer that at the Hippodrome she “didn’t have one of these, because opera singers didn’t need the microphone. You sang.” Richard Yarborough recalls that although he never heard his great-aunt sing in a formal setting, around the house she would regularly burst into operatic song: “It was almost a non sequitur. For whatever reason, she would do a snatch of a song, and of course it was always an opera.” Her voice, he remembered, was “booming” and powerful. It was also deep: “If I had to identify the register it wouldn’t have been soprano. It wasn’t very high. It struck me as a much deeper voice. Alto or something like that.” While Jarboro’s lower vocal register might be attributed partially to her age and the spontaneity of these performances, this description also coheres with earlier critics’ characterization of her voice as commanding and able to dominate the room she was in, be it the public space of a massive auditorium or the private space of a family member’s living room.

The interior of the Hippodrome, pre-1923

Inspired by the magnitude of Jarboro’s achievement, African American critics imagined her debut as Aida in what the American Studies scholar Josh Kun might call “audiotopian” terms, which cast Jarboro as concomitantly a singer, a celebrity, and a symbol. In a particularly poignant framing published in the Chicago Defender, Salem Tutt Whitney recounted that as he read the program for Jarboro’s performance, “The wonder of it all filled my eyes with tears and blinded my sight so that I could not see the names of those wonderful white artists, whose love for their art and devotion to their art ideals, completely erased all thought of racial prejudice, and in so doing proved that art is universal and international.” Whitney’s overwhelming emotion literally blinded him to the existence of the color line, presaging a future in which race was not authenticating but irrelevant. Importantly, this was a mode of universalism that did not require the erasure or transcendence of race, but rather insisted that racial difference could not justify inequality of musical opportunity.

Lucy Caplan is a scholar and critic based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This essay is adapted from her first book, Dreaming in Ensemble: How Black Artists Transformed American Opera (Harvard University Press). Pre-order the book here.