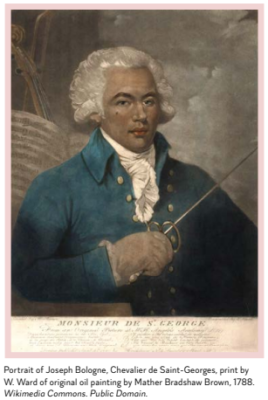

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges’ legacy is broad.

He was a biracial Frenchman, child prodigy as both a champion fencer and a virtuoso violinist, and later a celebrated and sought-after music director, composer, and officer in the French Revolution. He lived during a time that was full of innovation amid great political struggle and war across the Western world.

Joseph was born on Christmas Day in 1745 on a coffee and sugar plantation on the Caribbean Island of Guadeloupe to Georges Bologne de Saint-Georges and a teenaged, enslaved Senegalese woman named Anne, known as Nanon. Despite being married to a white French woman, Georges – a white French nobleman originally from Angoulême – acknowledged and claimed his son by giving Joseph his surname. When Joseph was barely two, Georges fled to France with Nanon and their son to escape an accusation of murder after a duel where his opponent was only superficially wounded by the épée puncture but died of tetanus. They returned to Guadeloupe following a royal pardon two years later, and all three of them traveled back to Georges’ hometown in France when Joseph was seven so he could begin his formal education at a Jesuit boarding school. After two years of boarding school, Joseph’s parents returned, and the three of them moved to Paris, where he enrolled at a private fencing academy and continued his violin study, also learning horseback riding, dancing, and all the skills expected of a French nobleman’s son. He was a quick study at fencing and was barely sixteen when he beat one of the best fencing masters in all of France in a public match. At age 21, his reputation as a swordsman earned him a position as an officer in the King’s bodyguard at Versailles, and the title of Chevalier, or knight.

Joseph was born on Christmas Day in 1745 on a coffee and sugar plantation on the Caribbean Island of Guadeloupe to Georges Bologne de Saint-Georges and a teenaged, enslaved Senegalese woman named Anne, known as Nanon. Despite being married to a white French woman, Georges – a white French nobleman originally from Angoulême – acknowledged and claimed his son by giving Joseph his surname. When Joseph was barely two, Georges fled to France with Nanon and their son to escape an accusation of murder after a duel where his opponent was only superficially wounded by the épée puncture but died of tetanus. They returned to Guadeloupe following a royal pardon two years later, and all three of them traveled back to Georges’ hometown in France when Joseph was seven so he could begin his formal education at a Jesuit boarding school. After two years of boarding school, Joseph’s parents returned, and the three of them moved to Paris, where he enrolled at a private fencing academy and continued his violin study, also learning horseback riding, dancing, and all the skills expected of a French nobleman’s son. He was a quick study at fencing and was barely sixteen when he beat one of the best fencing masters in all of France in a public match. At age 21, his reputation as a swordsman earned him a position as an officer in the King’s bodyguard at Versailles, and the title of Chevalier, or knight.

Joseph’s father returned to Guadeloupe after the Seven Years’ War and ensured Nanon and Joseph were given generous allowances so they could remain in Paris. However, since Joseph was considered an illegitimate child, French law prohibited him from inheriting his father’s property or his official status as a French nobleman. Even as he continued to be a celebrated fencing master, Joseph shifted his public career to his other love: music. He was likely as quick of a study in violin as he was with fencing, beginning his formal study at age seven, likely with some natural aptitude and affinity before that. Two years before he was knighted at age nineteen, concertos were being composed for him to premiere, and by age 25, he had composed several of his own. In 1771, he was appointed concertmaster of the Concert des Amateurs, a new orchestra in Paris, and the following year he debuted as a featured soloist premiering his own compositions. By 1773, he was appointed music director of the ensemble, and it quickly rose in acclaim to become the best-regarded symphony orchestra in France. Two years later, when the Paris Opéra was struggling both financially and artistically, Bologne was nominated to take over its artistic leadership, with no other French musician rivaling his skill and accomplishments. However, a few of the opera’s prima donnas penned a racist petition to the Queen protesting his nomination, and although Marie Antoinette was a great admirer of Bologne, politics prevailed, and the post was awarded to another man.

Following the rescinded nomination, Joseph Bologne’s notoriety and mastery only increased, and when lack of funding caused the Concert des Amateurs to fold, his new endeavors were supported by his rich network. His influential connections, including playwright Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais and Philippe d’Orléans, Duke of Chartres, helped found a new orchestra within their exclusive Freemason lodge made up of the best musicians in Paris, to which Bologne was appointed music director. The new Concert Olympique performed in the Théâtre du Palais-Royal, where Queen Marie Antoinette would frequent concerts, often without notice. The Queen also invited Bologne to perform in her private musical salons at Versailles.

Bologne began writing operas, and it took him a while to find his stride within this slightly different genre. His first opera, Ernestine, premiered in the summer of 1777, and although audiences liked the music, the opera closed shortly after its opening performance, citing a weak libretto. He found a new librettist, French playwright Desfontaines-Lavallée, to collaborate with for his second attempt, and they adapted one of his plays into an opera called La partie de chasse (The Hunting Party), which premiered in 1778. This opera was warmly received and had a longer run, but the score is lost to history, except for a few selections. While Bologne worked and lived on the premises with Madame de Montesson as music director of her private theater, he met her niece, Madame de Genlis, who was an author. Bologne’s third opera, and the only surviving one, L’Amant Anonyme (The Anonymous Lover), premiered in 1780 at Madame de Montesson’s private theater with a libretto by Desfontaines-Lavallée, adapted from Madame de Genlis’ novel of the same name. Bologne wrote three more operas after this one.

As the French Revolution loomed, Bologne lost his arts patronage and joined the Revolution as a citizen soldier in 1790, later serving as one of the first of the National Guard in Lille. While living in Lille, he continued to write music and conduct a local orchestra as well as compete in fencing duels. Bologne served the revolutionary cause for five years through many battles and was appointed captain of various citizen regiments, including France’s first regiment of all free Black men.

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges died in June 1799 at the age of 53 in Paris. He continued performing on the violin, composing, conducting, and fencing until his death. His legacy as an extraordinary Frenchman, gentleman, musician, and swordsman has survived and continues to be celebrated to this day.