[EXCERPT]

[EXCERPT]

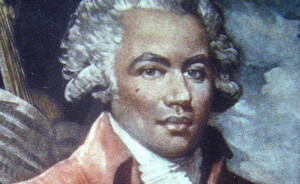

Joseph Bologne, “Chevalier de Saint-Georges” (ca. 1739-1799) was a Parisian celebrity, acclaimed swordsman, composer, violin virtuoso, and conductor of one of the best orchestras in Europe. He also fought in at least one, perhaps two revolutions. Bologne was born to a teenaged enslaved woman, Anne “dit Nanon” on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe. There is no record of his baptism, and primary sources have conflicting information regarding his date of birth. Bologne’s father, a wealthy plantation owner, brought the boy and his mother to Paris and introduced the young “Chevalier de Saint-Georges” into French society while ensuring he had the best education possible. While still a young man, he became famed for his fencing and remains an important figure in the history of the sport. A young Saint-Georges very publicly defeated a fencing master who taunted him with a racially derogatory name. After reaching the pinnacle of the art of swordplay, Saint-Georges turned his attention to composition, violin, and conducting.

Saint-Georges became concertmaster of the Concerts des Amateurs in 1771. He received widespread acclaim for his performances of his violin concertos. By 1773 he was named director of the Concerts des Amateurs and under his leadership the orchestra was considered among the best in Europe. Saint-Georges was such a success that the ill-fated queen Marie Antoinette invited Bologne to play with her at the palace. By 1775 he was the leading candidate for the most presitigious operatic post in France, director of the Académie Royale de Musique; however, some of the singers wrote a letter to the king stating that they would not work for a mixed-race conductor.

L’Amant Anonyme, comédie en deux actes mêlée de ballets, the only complete surviving opera of Saint-Georges, is based on a play by Stéphanie Félicité de Genlis (1746-1830). Madame de Genlis, a successful author and friend of Saint-Georges, was also the first woman to be appointed an official tutor to members of the royal family. There is very little recorded about the origins of the play or the opera, however we do know it was composed for the acclaimed private theater of Madame de Montesson (1738-1806). Saint-Georges was the music director of the theater and Madame de Genlis, the niece of Madame de Montesson, was well known to Saint-Georges. The opera premiered on March 8, 1780 according to the title page of the manuscript.

The play L’Amant Anonyme by Madame de Genlis was published in 1781. The play’s libretto was adapted for the opera by the well-known librettist François-Georges Fouques Deshayes, known as “Desfontaines” (1733-1825). It seems possible that the play was also performed at Madame de Montesson’s theater, perhaps Saint-Georges saw it and decided to set it to music. The aristocratic character of Dorothée from the play remains in the opera but does not sing; perhaps this character was designed for Madame de Montesson herself, as she often performed onstage in her theater.

The only source for the music is the manuscript at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, section musique, cote D-13863.[1] More work is needed to find additional clues about the identity of the copyist. We also do not know how directly this copy is linked to Saint-Georges. The manuscript contains many inconsistencies. Accidentals are frequently omitted, especially once a new key center is established. Slurring and articulation is also very inconsistent. Often the first violin has much less detail in its articulation than the second violin, even when they play the same music in octaves. This may be a sign that this score was copied from performance parts. Saint-Georges would likely have conducted performances from the concertmaster position, and may not have needed to write his own bowings and articulations into the first violin part. This could be a sign the manuscript was made soon after – or indeed in preparation for – the 1780 performance.

The plot of L’Amant Anonyme consists of a love triangle involving only two characters. Madame de Genlis achieves this unusual situation through the heroine Léontine believing that her friend Valcour and her secret admirer are two separate people. Léontine, a widow from an arranged marriage in her teenage years, resists the suggestion that she should give love another try. As a land-owning widow, Léontine is personally and financially independent, a true rarity for an 18th-century woman.

The opera highlights her powerful position with the Chorus in Act I, Scene iv “Chantons, célébrons notre dame.” This movement imitates some of the laudatory language in the prologues of older French operas, originally designed to curry favor with the composers’ patron, Louis XIV. Léontine is an untraditional feudal lord, perhaps due in part to the fact that the opera was written nine years before the beginning of the French revolution. The action occurs completely on Léontine’s estate, as Valcour (whom contemporary audiences would have recognized as being both newer to the nobility, and as holding a lower rank than Léontine)[2] struggles to muster the courage to declare his feelings.

In his comprehensive study of the Bologne’s life, Gabriel Banat suggests that Madame de Genlis may have written this play specifically for the Chevalier de Saint-Georges to set to music.[3] Banat also proposes that Valcour’s struggle and fear of rejection could have been modeled on the fear Saint-Georges may have felt trying to declare his feelings to any romantic interest within a system that literally forbade him to marry in his social circle.[4] However, it is not entirely clear the play was written for the Chevalier, and indeed there is an indication at the end of the play that the final words should be sung to the music of another composer.

In the 1781 stage play, Jeannette ends the evening by singing couplets in a peasant dialect of French, which the script notes are to be sung to the tune of the opening Rondeau from the opera Les Trois Fermiers by the composer Nicolas Dezède (c.1740-1792).[5] The use of dialect is quite interesting for French theater of the time. This unusual, informal language may reflect the influence of the recent rediscovery of Shakespeare, the coming revolution, or the literary Sturm und Drang movement. Saint-Georges also uses the methods of Sturm und Drang to present Léontine’s internal struggles as valid and dramatic. The musical heart palpitations in the Act II, Scene v Trio are especially notable in this regard, along with the music of the Ariettes in Act I, Scene iii and Act II, Scene i.

While Saint-Georges was extremely successful during his life, his legacy suffered due to state-sponsored racism. Alain Guédé explains in his book on Saint-Georges that “Napoleon Bonaparte reinstated slavery on May 20, 1802, having drowned Toussaint-Louverture’s young Haitian democracy in a sea of blood. This was a second death for ‘the [B]lack Mozart,’ as Saint-Georges was called in the years immediately following his death.”[6] Guédé goes on to say that people of color who had produced work showing “serious artistic endeavor were dismissed or banished from thought”[7] during the time of Napoleon. We hope this edition will help facilitate performances of a work so unjustly suppressed by systematic racism.

George N. Gianopoulos

Stephen Karr

Leila Núñez-Fredell

Mishkar Núñez-Fredell

Los Angeles, September 2020

[1] A reproduction of the manuscript was published by Pendragon Press in 1984 and is in the public domain.

[2] Isola Charlayne Jones “Observations and Insights into the Life and Vocal Work of Joseph Bologne (Chevalier de Saint-Georges)” (DMA diss., Arizona State University, 2016), 33-34.

[3] Banat’s book on Saint-Georges remains the most comprehensive study of the composer, although it is unfortunately tinged with racist sentiment. Gabriel Banat, The Chevalier de Saint-Georges, Virtuoso of the Sword and the Bow (Hillsdale: Pendragon Press, 2006), 233.

[4] Gabriel Banat, The Chevalier de Saint-Georges, 237.

[5] Stéphanie Félicité de Genlis “L’Amant Anonyme” in Thêatre de société ; Par l’Auteur du Thêatre à l-usage des jeunes Personnes. 7 Vols. (Paris: Lambert and Baudouin, 1781), 181-318. There is also a modern reprint of L’Amant: Stéphanie Félicité de Genlis, L’Amant Anonyme, ed. Paul Fièvre (Paris: LeCointe et Durey, 2019).

[6] Alain Guédé, Monsieur de Saint-Georges, Virtuoso, Swordsman and Revolutionary, trans. Gilda M. Roberts (New York: Picador-St. Martin’s Press, 2003), 262.

[7] Guédé, Monsieur de Saint-Georges, 262.