Prior to World War I, upper-class Protestant gay men and lesbians were accepted into the highest levels of Boston society. But after the War ended in 1918, a shift in public attitudes about homosexual people brought an end to the tolerance and started a series of purges and police actions that lasted through 1920. One of these purges was a secret court set up at Harvard to identify and expel gay students. The swiftness and strong actions of this court underscored a new wave of intolerance that began a 60-year period of repression.

As students poured back into Harvard after the end of World War I, the gay scene at the college exploded. As is true at many colleges, raucous late-night parties were held in students’ rooms. But Harvard’s gay parties featured men in drag and visitors who were picked up in Boston bars. Some of the parties were loud affairs, others were sedate cocktail events. But no matter the mode of partying, the informal network of gay students provided each other with entertainment and social support. Groups of students often went out to Boston bars together.

One of those students who partied on and off campus was Cyril Wilcox. A sophomore and a lackluster student, Wilcox was in a troubled relationship with Harry Dreyfus, the owner of a Beacon Hill speakeasy frequented by gay people. When Wilcox tried to break off the affair, Dreyfus threatened to go to Harvard authorities and denounce him. Under intense stress, Wilcox told the university he couldn’t take his spring exams and was instructed not to bother coming back. Wilcox committed suicide in May 1920 at his parents’ house in Fall River, Massachusetts.

Shortly after Cyril’s death, a letter from Harvard student Ernest Roberts arrived for him. It contained substantial gossip about who was trying to sleep with whom at the College. Soon after another letter arrived implicating more students. Enraged, either by homophobia, or the attempts to expose peoples’ private lives, or by the fact that Cyrus was threatened by an older man, Wilcox’s brother went to see Dreyfus and beat him up. He then went to Acting Dean Chester Greenough to demand justice and asking for the men implicated in the letters to be expelled. Greenough consulted with Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell, who authorized a secret court of College officials to investigate allegations and take appropriate actions against gay students. The witch hunt was on.

Dozens of students were called in one by one to answer questions before the court. Some were implicated in the original letters Dreyfus instigated, others became suspects when their names came up in testimony. None were represented by lawyers and none knew what kind of testimony might save them or cause their academic careers to end.

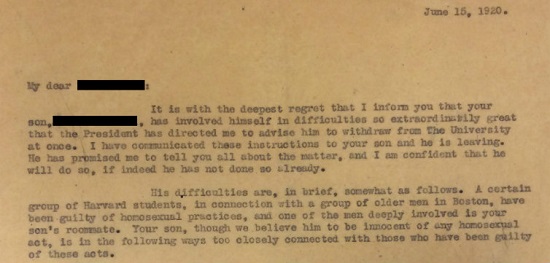

For the most part, students who confessed to homosexual behavior were permanently expelled. Those who did not were either exonerated or allowed to come back to Harvard after a year or two of forced leave. Expelled students were forbidden to step foot in Cambridge, though the College had no legal grounds to do this. The Dean wrote letters to the students’ parents, outlining the behavior that led to their sons’ expulsions.

When all was said and done with the hearings, seven young men were expelled. An eighth evaded the court’s justice by committing suicide. A teaching assistant and an assistant professor were fired. Two students were found guilty of tolerating the gay behavior of others and were also suspended for one to three years. But college officials at the time were not content to simply expel the men. Letters were placed in their files so if they tried to apply to another university, the explicit reason for their expulsion was communicated to admissions officers. Potential employers also were told why these young men were expelled. As a result, the men never graduated from any college and were forced into unconventional careers.

The court remained a secret for almost 90 years until an enterprising Harvard Crimson reporter found a reference to the court in the university archives, and was given a redacted copy of its papers. Though the university ultimately apologized, Harvard refused to grant diplomas to the expelled students, citing its policy not to award posthumous degrees.

Fellow Travelers opens November 13, 2019 and runs through November 17. Purchase tickets today at blo.org/fellow-travelers and follow along on social media using #FTBLO

About the Author:

Russell Lopez is on the Boston Lyric Opera Board of Advisors and a Board Member of The History Project (historyproject.org) and organization focused exclusively on documenting and preserving the history of New England’s LGBTQ communities and sharing that history with LGBTQ individuals, organizations, allies, and the public.

In the frame:

Photo of Cyril Wilcox, a Harvard undergrad, committed suicide in Fall River in May 1920. Photo courtesy of: Harvard University

Court redacted letter written to the parents ofa Harvard University student. Photo courtesy of: thefire.org

Screenshot of the article written by Amit R. Paley for The Crimson. Article found at: thecrimson.com