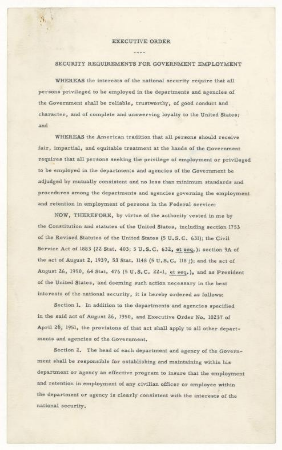

The overwhelming threat hanging over the heads of the characters in Fellow Travelers was known as Executive Order 10450, which prohibited the federal government from hiring gay and lesbian people. Signed by President Dwight Eisenhower in April 1953, the Executive Order was drafted by Robert “Bobby” Cutler, a noted Bostonian who was the first person appointed as National Security Advisor to the President of the U.S. It remained in full force until 1973 and was only revoked in its entirety in 2017.

In the years after World War II, many in the United States feared that Communist agents and sympathizers had infiltrated the government in order to turn over nuclear secrets and destroy the American way of life. Led by the now-notorious Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy (a character in the opera), this so-called “Red Scare” resulted in thousands losing their jobs as Democrats and moderate Republicans were pressured to denounce suspected sympathizers in the State Department and other branches of government. McCarthy used televised hearings and loud threats to create panic and destroy people he imagined as his enemies.

Senator McCarthy used the same tactics to force the federal government to fire gay and lesbian employees. Dubbed the “Lavender Scare,” these efforts represented the crest of federal anti-gay efforts that began 40 years earlier during World War I when the Secretary of the Navy ordered cities around the country to shut down gay bars, and arrest gay men and lesbians.

In Boston during that time, this order resulted in police apprehending men in Scollay Square and the South End, and raiding private homes in Beacon Hill and the Back Bay. Newspaper accounts of the time reported the streets and bars in Scollay Square were empty because people feared arrest. The repression abated somewhat after World War I ended; regardless, thousands of people lost their jobs and homes because of arrests and anti-gay bigotry in the interwar years.

When World War II ended, the federal government redoubled its efforts to purge gays and lesbians from its ranks. McCarthy (who, both then and now, was suspected of hiding his own gay existence) and other anti-gay zealots had two objections to the government employing LGBTQ people: 1) the indication that such people were “morally unfit”; and 2) even if loyal to the country -they were “vulnerable” to being blackmailed. There were never reports of gays and lesbians being blackmailed and turned into Soviet agents, but homophobia was so strong throughout society, all gay and lesbian people were considered to be suspect.

In the post-World War II era, virulent anti-gay feelings were common among many in straight society. Homosexuals were routinely denounced by the clergy, colleges expelled anyone suspected of being gay, and parents often disowned their gay or lesbian children. There were few out gay or lesbian people and those who were questioned about it simply denied their sexual orientation.

While to some extent he stood up against McCarthy’s red baiting, Dwight Eisenhower did not resist pressure to ban the employment of gays and lesbians. Within the first few weeks of being sworn into office, he asked Bobby Cutler to draft what became Executive Order 10450. Cutler had been an aide to Eisenhower during World War II and was a close personal assistant during Eisenhower’s 1952 presidential campaign. A lifelong Republican, Cutler was a staunch member of its establishment throughout the 1950s.

Cutler was born in Brookline, died in Concord, Mass., and lived at Beacon Hill’s Somerset Club for much of his life. A Harvard graduate, a banker, a Trustee of Peter Bent Brigham Hospital and an author of novels about Beacon Hill, Cutler was also gay. According to his diary and personal papers, (and, as documented in the 2018 book, Ike’s Mystery Man by Peter Shinkle) he was hopelessly in love with Skip Koons, a handsome staffer at the National Security Council, who was 32 years his junior.

Although it appears the relationship was never consummated and his love was likely unrequited, Cutler swooned whenever they were together, even when out to dinner. Cutler’s homosexuality was well known in Washington circles; even Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. — Richard Nixon’s 1960 running mate — knew it. When public rumors grew so loud as not to be ignored, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover investigated and exonerated Cutler, publicly declaring him to be straight. (Hoover’s own sexuality, and his physical relationship with protégé and top FBI deputy Clyde Tolson has long been a subject of cultural inquiry.)

We can’t really know why Cutler and other prominent closeted gay men contributed to the crackdown on gays and lesbians during the 1950s. It may be that they internalized the strong hatred of LGBTQ people so prevalent in those days. Or they might have turned in others in order to save themselves; by being publicly anti-gay they turn suspicions elsewhere. Certainly, the vehemence with which they implemented and carried out the destruction of other gay people suggests deep psychological stresses.

The Executive Order so many of these men promoted and upheld stated that “immoral conduct” and “sexual perversion” were grounds for dismissal from the federal government. Furthermore, it authorized authorities to reopen investigations of people who had already been hired. Many states copied the federal order with similar regulations. There were no laws to protect gay men and lesbians from losing their jobs.

The effects of the order were devastating. Thousands of people lost their jobs. During the 20 years when the order was most vigorously enforced, more people were fired for being gay than for being Communist sympathizers.

Gay federal employees were forced deeper into the closet. Some gay men and lesbians married each other to provide support and cover. Other gay men married straight women, hoping to live surreptitious gay lives when they could. Some gays and lesbians, once identified and fired, committed suicide. Others were disowned by their families or evicted by their landlords, and many found alternative job opportunities were unavailable to them when interviewers found out why they left federal service. Across the country, public campaigns to fire known and suspected homosexuals combined with police sweeps of gay bars and public cruising areas. As a result, an entire generation was scarred. The Executive Order made public disclosure of sexual identity dangerous; only those with little to lose risked exposure.

Executive Order 10450 began to be curtailed in 1973 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that gay civilian employees of the federal government who did not need security clearances could not be fired without other causes. It took two years for the federal government to adopt policies to end the automatic firing of gays and lesbians. LGBTQ people were allowed employment only on a case-by-case basis.

Additional improvements were slow in coming. The State Department began allowing LGBTQ people in the Foreign Service in 1977. Military policy was changed to “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in 1994. Automatic denial of security clearances was ended in 1995 and President Barack Obama signed the complete repeal of Executive Order 10450 on his last day in office, more than six decades years after it went into effect.

However, these freedoms extend only to federal hiring. As of today, in 26 states, LGBTQ people can be fired simply for being who they are.

As demonstrated in Fellow Travelers, the pressures on gay men and lesbians in the 1950s were enormous. People became aware of their sexualities in a time of ignorance and fear, and if they acted on it, the consequences could be devastating. It is these tensions that power the opera.

Fellow Travelers opens November 13, 2019 and runs through November 17. Purchase tickets today at blo.org/fellow-travelers and follow along on social media using #FTBLO

About the Author:

Russell Lopez is on the Boston Lyric Opera Board of Advisors and a Board Member of The History Project (historyproject.org) and organization focused exclusively on documenting and preserving the history of New England’s LGBTQ communities and sharing that history with LGBTQ individuals, organizations, allies, and the public.

In the frame:

Hadleigh Adams as Hawkins Fuller is interrogated during Minnesota Operas production of Fellow Travelers. Photo by Dan Norman

The cover of Peter Shinkle’s book Ike’s Mystery Man: The Secret Lives of Robert Cutler Photo courtesy of Amazon.com

Page one of Executive Order 10450: Security Requirements for Government Employment Photo courtesy of: National Archives and Records Administration. Office of the Federal Register. 4/1/1985