Rumor has it that Edgar Allan Poe modeled the House of Usher on a dwelling in Boston with a gruesome secret. The Tremont Street home of eighteenth-century bookseller Hezekiah Usher (located just a few blocks from the house where Poe was born, in 1809) was demolished in 1830, and two bodies were said to have been discovered in the basement, locked in a ghastly embrace. But that is just a rumor. The precise origins of Poe’s celebrated story remain elusive – like so many elements of the work itself.

“The Fall of the House of Usher” is shrouded in uncertainty. On one level, it is a straightforward, albeit horrific, tale that begins when the narrator is summoned to the disintegrating house of Roderick Usher, a long-lost friend who, along with his sister, Madeline, is suffering from a calamitous illness. Scrutinized for allegorical meaning, the story has also been understood as a meditation on the dualities of the human psyche, a Gothic tale of supernatural danger, or a commentary on the collapse of an old-guard aristocracy in the young United States. Poe relies less on concrete detail than on what Charles Baudelaire (who translated his works into French) called “indefinite sensations.” Because the story hovers in the uncanny space between fact and myth, it is difficult to determine what, exactly, it means: it insists on keeping its secrets.

Such enigmatic mystique is at the heart of the tale’s enduring allure. First published in a literary magazine in 1839, “The Fall of the House of Usher” has inspired an outpouring of adaptations by other artists and writers. There have been several cinematic retellings, from an experimental French silent version (1928) to a low-budget American production (1960) to a Czech stop-motion animation (1982). In the realm of opera, it first attracted the attention of Claude Debussy, who worked on a score for years but never completed it. Philip Glass’s 1988 opera of the same name, with a libretto by Arthur Yorinks, became the first full operatic adaptation of Poe’s story.

Such enigmatic mystique is at the heart of the tale’s enduring allure. First published in a literary magazine in 1839, “The Fall of the House of Usher” has inspired an outpouring of adaptations by other artists and writers. There have been several cinematic retellings, from an experimental French silent version (1928) to a low-budget American production (1960) to a Czech stop-motion animation (1982). In the realm of opera, it first attracted the attention of Claude Debussy, who worked on a score for years but never completed it. Philip Glass’s 1988 opera of the same name, with a libretto by Arthur Yorinks, became the first full operatic adaptation of Poe’s story.

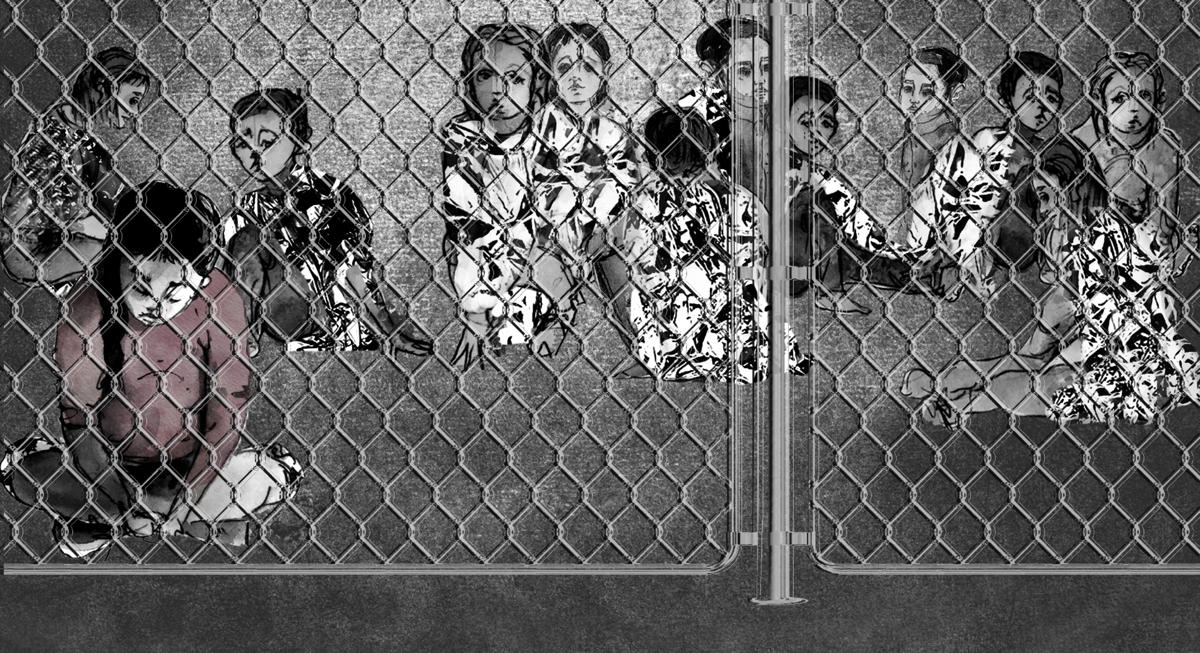

Boston Lyric Opera’s production adds to and expands upon this history of adaptation, creating a multilayered story that introduces new narrative elements while retaining the essential ambiguity at the core of the original. It embeds Glass’s opera within a story about a young Guatemalan girl named Luna, who is detained at the U.S.-Mexico border. Evoking the experimental style of arthouse film, it forgoes  conventional narrative in favor of a dreamlike combination of music; stop-motion animation that narrates Poe’s original story; hand-drawn animation representing Luna’s perspective; and found archival footage that speaks to broader conceptual issues: family, memory, grief, migration, and the perpetually vexed meaning of American identity. These additional layers bring Poe’s story closer to our own time, in terms of both technological innovation and social resonance. In doing so, they encourage viewers to consider what it means to understand the opera’s characters as figments not only of Poe’s nineteenth-century imagination, but also of Luna’s twenty-first-century perspective. In this reimagining, as in Poe’s original, the preponderance of dramatic layers may obscure more than it clarifies. And that is precisely the point. Obscurity, or a refusal to offer easy interpretive answers, is what enables the opera to offer such a powerful meditation on what it means to be American, to be trapped, to be at peace, to struggle, to be free.

conventional narrative in favor of a dreamlike combination of music; stop-motion animation that narrates Poe’s original story; hand-drawn animation representing Luna’s perspective; and found archival footage that speaks to broader conceptual issues: family, memory, grief, migration, and the perpetually vexed meaning of American identity. These additional layers bring Poe’s story closer to our own time, in terms of both technological innovation and social resonance. In doing so, they encourage viewers to consider what it means to understand the opera’s characters as figments not only of Poe’s nineteenth-century imagination, but also of Luna’s twenty-first-century perspective. In this reimagining, as in Poe’s original, the preponderance of dramatic layers may obscure more than it clarifies. And that is precisely the point. Obscurity, or a refusal to offer easy interpretive answers, is what enables the opera to offer such a powerful meditation on what it means to be American, to be trapped, to be at peace, to struggle, to be free.

Glass’s music exemplifies these ambiguities. The composer has described his work as a “poetic meditation” on Poe’s story, and that oblique approach can be heard in the score’s transfixing effects. Written in Glass’s iconic style, it pulses and undulates. Sensations supersede events: rather than conveying a progression from beginning to middle to end, the music creates a sense of pervasive atmospheric mystery. Yet as in Poe’s original story, no detail is extraneous. When William first enters the House of Usher, for instance, his entrance is announced by an ominous short-short-short-long figure, evocative of the “Fate” motif of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony; that sound morphs into a repeated orchestral motif that underlies the uneasy remainder of the scene. It is a subtle but stark reminder that the door on which William knocked (and, by extension, the house itself) are inseparable from the actions of the characters within its gates. The motif asks listeners to wonder: are these characters fated to disintegrate along with the house? To what extent can they – and Luna, similarly confined in the detention center – control their destinies?

In Glass’s score, the character of Madeline Usher vocalizes wordlessly throughout the opera. One literary critic has termed her a “dead woman wailing,” a not-quite-human, not-quite-alive figure who haunts the scene, making her presence known through sound rather than words. (At one point, William even mistakes the sound of her voice for that of the wind, further distancing her from her humanity.) Her musical contributions are emotionally rich, but they reveal little about who she is; like the character of Poe’s imagination, and like so many other operatic women, she is treated as less or other than human, and as doomed to inevitable suffering. The experimental style of BLO’s production complicates this tradition by intertwining Poe’s characters’ story with Luna’s experiences. Like Madeline, Luna is wordless, opting to share her perspective through other means. But unlike Madeline and her twin Roderick, who are figuratively and then literally entombed in their ancestral home, Luna is a young girl trapped in limbo at the border, far from her first home of Guatemala and seeking to make a new one in the United States. Although the Usher family and Luna are each, to some extent, powerless to control their destinies, Luna is far more human. We are privy to details of her past, her family, and her imagination, which she holds close under precarious circumstances. Thrust into a traumatic and dehumanizing situation, Luna becomes a storyteller, using a dollhouse to imagine another, distant world. Her story makes the vague horrors of Poe’s original tale far more concrete: the nebulous sickness and disintegration of Poe’s short story transmogrify into the all-too-real crises of family separation, violence, and xenophobic cruelty.

In Glass’s score, the character of Madeline Usher vocalizes wordlessly throughout the opera. One literary critic has termed her a “dead woman wailing,” a not-quite-human, not-quite-alive figure who haunts the scene, making her presence known through sound rather than words. (At one point, William even mistakes the sound of her voice for that of the wind, further distancing her from her humanity.) Her musical contributions are emotionally rich, but they reveal little about who she is; like the character of Poe’s imagination, and like so many other operatic women, she is treated as less or other than human, and as doomed to inevitable suffering. The experimental style of BLO’s production complicates this tradition by intertwining Poe’s characters’ story with Luna’s experiences. Like Madeline, Luna is wordless, opting to share her perspective through other means. But unlike Madeline and her twin Roderick, who are figuratively and then literally entombed in their ancestral home, Luna is a young girl trapped in limbo at the border, far from her first home of Guatemala and seeking to make a new one in the United States. Although the Usher family and Luna are each, to some extent, powerless to control their destinies, Luna is far more human. We are privy to details of her past, her family, and her imagination, which she holds close under precarious circumstances. Thrust into a traumatic and dehumanizing situation, Luna becomes a storyteller, using a dollhouse to imagine another, distant world. Her story makes the vague horrors of Poe’s original tale far more concrete: the nebulous sickness and disintegration of Poe’s short story transmogrify into the all-too-real crises of family separation, violence, and xenophobic cruelty.

What can an opera, a film, or a short story tell us about American identity? A return to the original text is little help here, as Poe was a skeptic with respect to the idea that art could or should shape national identity. In an era when many of his fellow American artists were preoccupied with defining the nation as distinct from European counterparts (and also with erasing the presence of enslaved and indigenous people in order to center a white American identity), he expressed ambivalence about the viability of that project. “The Fall of the House of Usher” reflects that ambivalence. While some critics have proposed that the story is a critique of Europe insofar as the Ushers’ decline represents the fall of aristocracy in the young, democratic United States, others (rumors of a Boston setting notwithstanding) have suggested that the story may not even take place within the nation’s borders.

Nearly two centuries later, the question of what it means to create American art remains far from settled. Luna’s story, like Poe’s, has a fraught relationship with the meaning of American identity. It takes place in the border space between the U.S. and Mexico while also hovering on the border between truth and imagination. Even more significantly, although Luna idealizes the United States and seeks to live within the nation’s borders, others refuse to let her do so, raising the question of who – Artists? Border agents? Communities? – gets to decide what it means to be American. Like the dolls in Luna’s dollhouse, the very concept of national identity is created partially in the realm of the imagination, a collective idea rather than an empirical reality. Yet that same unreal, uncertain quality is what makes art such a powerful space for contemplating American identity – and, potentially, for imagining a more hopeful national future. Truth may be stranger than fiction, but sometimes the strangeness of fiction can illuminate deeper, more profound truths about our nation and ourselves.

About the Author:

Lucy Caplan holds a Ph.D. in American Studies and African American Studies from Yale University. The recipient of the Rubin Prize for Music Criticism, she teaches in the History and Literature program at Harvard College and writes frequently about music and culture.

In the Frame:

A black and white illustration of a large house surrounded by a low wall and a few trees. It reads “Mansion erected by Hezekiah Usher in 1684 on what is now the corner of Tremont Street and Temple Place.” Courtesy of: Rossiter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Philip Glass, and older white man with dark hair in a black vest over a red shirt is painted is large brush strokes. Courtesy of: Alvarezroure, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Luna, a young girl in a pink shirt an patterned pants, stands in a yard surrounded by a fence with barbed wire on top while holding a box. The image is a drawing in black, white, and grey with the exception of Luna’s clothes that are a light pink. Image from: operabox.tv/Boston Lyric Opera

Madeline Usher, a doll wearing a flower crown and white, lace, floor-length dress, hovers in an open window with curtains blowing in the wind on either side of her. Image from: operabox.tv/Boston Lyric Opera

Luna sits cross-legged to the left of the frame behind a chain link fence. There are other people huddled under shining silver blankets behind her. She looks sadly down at the ground. Image from: operabox.tv/Boston Lyric Opera