One day, a New York Times article made the striking announcement that there was a “Jazz Opera in View for the Metropolitan.” The company expressed interest in producing an opera of the “modern American type.” Branching out beyond the European canonical repertory, the article explained, was a necessary innovation which would “bear important fruit in the near future.” If these sentiments – a desire to expand the repertory, a commitment to foregrounding new work – sound familiar, then it may come as a surprise to learn that this article was published nearly a century ago: on November 18, 1924. What’s more, its focus on a “jazz opera” suggests that the idea of bringing jazz into the opera house is hardly new. Rather, the concept is nearly as old as jazz itself.

Champion enters into this century-long tradition in which opera and jazz intermingle. Yet it’s important to note that Terence Blanchard describes his work not as “jazz opera,” but rather as an “opera in jazz.” The distinction is significant: it suggests that for Blanchard, jazz is not just a modifier of opera but an essential context for the entire work. The composer has elaborated, “I’m trying to take American folklore that I know, that I’ve experienced, which is jazz, and bring that into the operatic world, but not totally use the entire piece to make a statement about jazz.”

Complicating matters further is the fact that both “opera” and “jazz” resist easy definition. Each describes as expansive, stylistically diverse art form whose parameters have changed dramatically over time. Their respective definitions are also bound up with questions of geographic and racial identity. Jazz – sometimes called “America’s classical music” – builds upon diverse local traditions within Black musical life; opera’s roots are in Europe, and the art form’s major institutions have historically excluded people of color. Even though both genres have long attracted artists and audiences of myriad backgrounds, these historical associations are vital to understanding what happens when the two intertwine.

Among the innumerable works which combine jazz and opera in some capacity, a few early examples help illuminate these complex dynamics. The 1924 call for a “jazz opera” at the Met, in fact, offers a prime illustration. The Times reported that the company had three potential composers in mind for this new piece: Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, and George Gershwin, all white men renowned for their work in non-operatic genres. The narrow makeup of this list was perhaps unsurprising, given a long history within opera in which supposedly “exotic” or racialized music entered the opera house via the compositional perspective of white male composers.

Harry Lawrence Freeman, courtesy Columbia University Libraries.

Yet the call for a “jazz opera” resonated with others as well. For instance, it sparked the imagination of Harry Lawrence Freeman, one of the most remarkable figures in U.S. opera history. Freeman, who was born to a family of free Black landholders in Cleveland and moved to New York around 1910, had been composing opera since the 1890s. A Wagner aficionado with an immensely ambitious vision for representing Black life on the operatic stage, Freeman had rarely before been interested in merging jazz with opera. Yet he saw an opportunity, and quickly began work on a piece he called American Romance: A Jazz Opera. Unlike most of Freeman’s earlier works, which featured Black characters and were set in various locales from ancient Egypt to Mexico, American Romance told the story of a white American family in 1920s New York. The opera even featured a Wagner-inspired leitmotif called “jazz,” a punchy figure of sixteenth notes scattered atop an eighth-note bass. The opera never reached the stage, but it offers a tantalizing example of how African American composers were thinking about jazz and opera at this juncture.

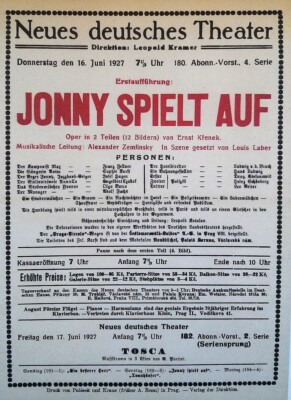

Freeman’s work also implicitly spoke back to a growing fad for “jazz opera” among white American and European composers. Gershwin’s Blue Monday, written in 1922, was a short work, subtitled “Opera a la Afro-American,” that was originally intended to be part of a Broadway revue. Loosely inspired by Pagliacci, it begins with the proclamation that the audience is about to “Love! Hate! Passion! Jealousy!”. It proceeds to offer an over-the-top dramatic narrative, bolstered by a score –orchestrated by the Black composer Will Vodery, a mentor of Gershwin’s – that includes jazz-inspired recitatives and spoken dialogue alongside Italianesque arias. The piece’s racial politics are troubling: it was first performed by a cast of white actors wearing blackface makeup, and it featured racial slurs and offensive stereotypes within its plot. A few years later, Austrian composer Ernst Krenek made a splash with Jonny spielt auf, which premiered in Leipzig in 1927. A tale of an American jazz violinist, the opera was immensely popular with European audiences: it was performed nearly 500 times in Germany alone during the year after its premiere. When first performed in the United States, in 1929, it became another vehicle for operatic blackface on the part of white singers in the title role. As a number of African American critics at the time noted, there was a deep irony at work here: these operas embraced and capitalized upon the explosive popularity of jazz, even as operatic institutions continued to exclude Black artists from the stage.

Poster for Jonny Spielt Auf, Wikimedia Commons.

But the encounter between jazz and opera never took place on a one-way street. Take Louis Armstrong, who, when he first began buying records around 1917, gravitated toward both pop songs and the highest-profile opera singers of the day: Caruso, Tetrazzini, Galli-Curci. As a member of Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra, Armstrong recalled, he “got a solo on stage, and my big thing was Cavalleria Rusticana.” That fondness for opera can be heard in his recordings, too. One scholar suggests that in his wildly popular 1928 recording of “West End Blues,” Armstrong makes melodic allusions to Carmen, Rigoletto, and Eva Dell’Acqua’s soprano showpiece “Villanelle.” There’s also a Wagnerian “Tristan” chord hiding in plain sight in his recording of “Blue Again,” from 1931. At precisely the same time as opera audiences were listening to jazz within the context of newly composed works for the stage, jazz audiences heard snippets of opera cropping up within a flourishing new tradition. From the earliest days of “jazz opera,” then, the term had an expansive scope. Jazz met opera within the context of Black operatic composition, in white-authored works which welcomed jazz’s musical appeal more than its creators, and in the musical imagination of innovative jazz composers and performers.

This patchwork of histories continues to shape the relationship between jazz and opera today – particularly in a piece like Champion, the work of a composer with deep expertise and experience across both genres. Blanchard grew up in New Orleans, where his father was an amateur opera singer who liked to listen to arias around the house and sing them with friends. Long celebrated as a jazz trumpeter and film composer (the opera also reflects this facet of the composer’s estimable background in its cinematic pacing and rich atmospheric writing), he turned to operatic composition relatively recently, while at the zenith of a high-profile career. In Champion, which premiered in 2013, Blanchard does not so much seek to create a jazz-opera hybrid as to move fluidly across the disciplines. The opera features both a chamber orchestra and a jazz quartet, for instance, and makes occasional room for improvisation from the singers. The result is a work of textural depth, melodic complexity, and exciting dramatic momentum. It demonstrates that, nearly a century after the idea was first raised, “jazz opera” continues to provide a rich source of inspiration for today’s composers. As much as it looks toward the past, this “opera in jazz” also expands the art form’s future horizons.

Lucy Caplan, Ph.D., is a scholar and critic based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She teaches at Harvard University and is writing a book about African American opera in the early twentieth century.