Original post from The Iris: Behind the Scene at The Getty by November 1, 2014.

A glimpse at life in the ancient Roman provinces of Gaul through the lens of food, glorious food

One of a Pair of Cups with Centaurs (detail), A.D. 1–100, Roman, found at Berthouville, France. Silver and gold, 5 7/8 in. diam. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des monnaies, médailles et antiques, Paris

My passions for history and food often cause me to wonder how past cultures ate, drank, and relaxed. Recently I’ve been immersed in the history and tastes of ancient Rome, and Roman Gaul in particular.

Gaul was a vast area under the control of Rome that occupied the lands of modern-day France, Luxembourg, western Switzerland, Belgium, western Germany, and northern Italy. Gaul is also the subject of the exhibition Ancient Luxury and the Roman Silver Treasure from Berthouville.

The Rich and Famous of Ancient Gaul

Gaul fell under the control of Rome in the mid-first century B.C., when Julius Caesar defeated the local Celtic tribes. He charged local land-owning duumviri (the equivalent of the chief magistrates or consuls of Rome) with the administration of the territory’s four provinces called civitates (citizenries). The administrators of Roman Gaul were not allowed to collect taxes—only Roman officials could—so the building and maintenance of Gaul’s cities was largely dependent on local elites. They financed public works that enhanced city life.

The most important contribution of the elites of Roman Gaul was the forum, the city center with administrative buildings. They also erected warehouses, bathing establishments, theaters, and other buildings for spectacles, and took charge of organizing public festivals. Built in A.D. 90, the Roman amphitheater at Arles, in Bouches-du-Rhône, served as a public venue for chariot races and gladiatorial combats.

Roman amphitheater in Arles, France. Photo: scumdogsteev, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Besides funding civic architecture, a leading citizen’s status was elevated by making dedications in a sanctuary to a god or goddess. The exhibition Ancient Luxury and the Roman Silver Treasure from Berthouville presents silver treasures gifted by donors to a religious sanctuary near the modern town of Berthouville in Normandy. The sanctuary was dedicated to Mercury Canetonensis, a local version of the Roman god Mercury.

Nine vessels dedicated by Quintus Domitius Tutus, A.D. 1–200, Roman, found at Berthouville, France. Silver and gold. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des monnaies, médailles et antiques, Paris

Nine silver vessels in the Berthouville Treasure are inscribed with the name of a single donor, Quintus Domitius Tutus. We have little information on Quintus Domitius Tutus, though we know it’s possible he hailed from an illustrious Roman family. Perhaps Tutus was an officer stationed in northwest Gaul or a magistrate. Some scholars have suggested he may have owned a villa not far from the Berthouville sanctuary.

Life in an Ancient Villa

Imagine what it must have been like to arrive at a suburban villa at the end of a hectic day or week in the city. Just one look at the serenity of cultivated fields, forests, and meadows must have wiped away all traces of stress and fatigue. Yet the proprietor of such an estate could not rest for long, since he directed the work of agricultural laborers and artisans. Sales of products from on-site mills, mines, workshops, potteries, glassworks, and ironworks resulted in high profits for land-owning Gauls.

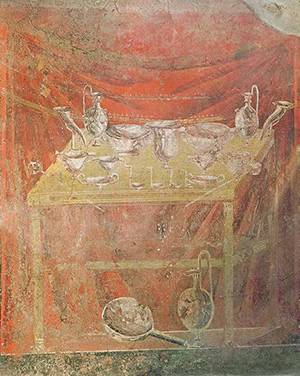

Wall painting of a table laden with paired silver vessels from the tomb of Gaius Vestorius Priscus at Pompeii

A hardworking and successful businessman also entertained and hosted banquets. Guests could immediately assess their hosts’ worth with just one glance around the triclinium (formal dining room). This wall painting of a table adorned with paired silver vessels is from the tomb of Gaius Vestorius Priscus at Pompeii. Do you notice the four ladles at the table’s edge?

At a banquet, ladles were used by slaves to transfer wine from a krater (large mixing vessel) to a skyphos (a drinking vessel with two lateral handles). During a feast, the villa’s host customarily served wine from his own vineyards. Fun side note: the Gauls invented the wine barrel, which was later imported to Rome.

Tastes of the Roman Table

Written sources such as the Roman recipe book De re coquinaria paint a vivid picture of what the ancient Romans ate, both in Italy and further afield in the provinces.

An aperitif such as mulsum, consisting of warm, spiced wine, would be served at the beginning of the meal. Among the various delicacies might be patina, a custard-like baked mixture of savory ingredients such as meat, chicken, or fish, herbs, olive oil, nuts, and wine. A sweet version with pears, eggs, honey, and spices could also be served.

Beef, mutton, lamb, game, fowl, seafood, and pork were the pièces de résistance of an elite meal. The fine salted hams of Gaul were considered specialty foods and were high on the list of coveted exports. Imported costly spices such as cumin, coriander, saffron, cinnamon, and pepper were relished not only for their flavor, but also testament to a man’s wealth. Garum, a condiment made from fermented fish, was added to many dishes.

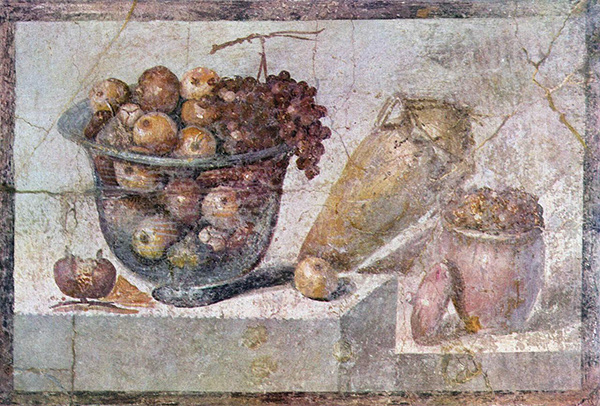

Wall painting from Pompeii (around A.D. 70) depicting autumn produce, grapes, apples, and pomegranates overflowing a large glass bowl, next to a tilting amphora and a terracotta pot of preserved fruit

On villa farms, cereals and legumes such as peas, lentils, and chickpeas were planted in rotation. Vegetables such as cabbage, squash, spinach, lettuce, and leeks were prepared in a variety of ways. Eggs were indispensable, and milk from sheep and goats produced a variety of cheeses, including regional specialties such as smoked cheese.

Finally, assorted fruit such as grapes, apples, pomegranates, preserved fruits, assorted nuts, and honey joined the gastronomic repertoire of a Roman table.

Most Romans did not banquet like the elites, of course. Most people subsisted primarily on grains and legumes. Both wheat and spelt were used in focaccia, bread baked on a hearth.

In this panorama of foodstuffs, I can see the origins of modern-day French fare: terrine (patina), Bouillabaise (a Provençal fish stew originating in Marseille in 600 BC), focaccia (in French, fougasse), petits pois (peas), and poireaux (leeks).

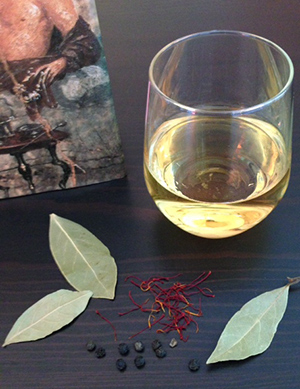

To taste for yourself a little of Roman Gaul, here’s a recipe for spiced honey wine. Cheers!

Recipe for Mulsum, Roman Spiced Honey Wine

Also known as Conditum paradoxum, from Apicius’s De re coquinaria

Ingredients

1 bottle dry white wine

¾ cup (6 ounces) clear honey

½ teaspoon ground black pepper

2 bay leaves

Pinch saffron threads

Directions

1. Pour 2/3 cup of the wine and the honey into a 2-quart saucepot and bring it to a boil.

2. Remove the saucepot from the heat and add seasonings to the hot wine; set it aside for 5 minutes.

3. After 5 minutes, add the rest of the wine.

4. Serve mulsum warm or transfer the mixture to a glass jar, cover, and refrigerate. As a modern variant, this drink can also be enjoyed cold over ice.