Norma is an opera with a reputation.

For nearly two centuries it has been admired as the finest of Bellini’s ten operas and the greatest opera composed during the bel canto era. So much so that other significant composers of Bellini’s time and afterwards have paid tribute. Liszt created a pugilistic fantasy for solo piano on themes from Norma. Chopin appropriated a piercing melody from the opera for the most poignant of his piano Etudes. (The Polish composer also wanted to be buried next to Bellini in a Paris cemetery, and he was.)

For nearly two centuries it has been admired as the finest of Bellini’s ten operas and the greatest opera composed during the bel canto era. So much so that other significant composers of Bellini’s time and afterwards have paid tribute. Liszt created a pugilistic fantasy for solo piano on themes from Norma. Chopin appropriated a piercing melody from the opera for the most poignant of his piano Etudes. (The Polish composer also wanted to be buried next to Bellini in a Paris cemetery, and he was.)

Wagner conducted a production of Norma in Riga in 1837 when he was only 24 years old; he also published a significant essay about the opera, praising the composer’s attention to text, his long-breathed melodies, and how his way of intertwining music and text was intrinsically dramatic and theatrical. Further, he wrote that Norma was worthy of comparison to Greek tragedy and the great classical operas of Gluck. Wagner also composed an additional aria for the bass that is occasionally inserted into the score.

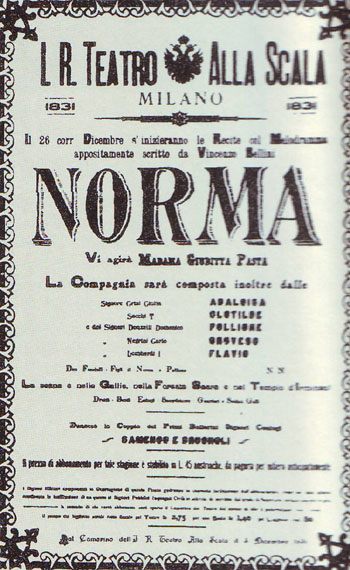

Nevertheless, the world premiere of Norma at La Scala in Milan on the day after Christmas in 1831 was not a success and the composer’s mood was dark – he called the performance “a solemn fiasco.” But the audience grew more receptive during the second performance, and it didn’t take long for the opera acquire traction and spread across Italy, Europe and the United States, where New Orleans hosted the American premiere in 1836. Within a few years, Norma had been translated into 17 languages.

Nevertheless, the world premiere of Norma at La Scala in Milan on the day after Christmas in 1831 was not a success and the composer’s mood was dark – he called the performance “a solemn fiasco.” But the audience grew more receptive during the second performance, and it didn’t take long for the opera acquire traction and spread across Italy, Europe and the United States, where New Orleans hosted the American premiere in 1836. Within a few years, Norma had been translated into 17 languages.

Nevertheless, it didn’t reach The Metropolitan Opera until 1890 when Lilli Lehmann sang the title role in German – by then Lehmann was the international favorite as Brünnhilde and Isolde, remarking to the press that it was far less stressful to sing all three Brünnhildes in Wagner’s Ring than to sing one Norma. The Met’s second performance took place in Boston, again with Lehmann. The critic from the Evening Transcript wondered why an opera that had been so popular for so long hadn’t been heard here in 15 years. In fact, gaps like that haven’t been uncommon outside of Italy.

With Norma, Bellini was certainly at the peak of his powers. He had labored over the score with diligence and drove the librettist Felice Romani crazy with his demands – Bellini knew exactly what he wanted and needed.

Wagner’s comparison of Norma to Greek tragedy was apt. The opera is based on a French play by Auguste Sommet, Norma, or the Infanticides. This fuses elements of Euripides’ Medea with a Druid episode in Chateaubriand’s then-recent novel, The Martyrs.

The principal events in the opera occur within the larger context of two clashing cultures, each of them vividly depicted in the music – the Druids mysterious in worship and barbarically ferocious in war; the Romans victorious in every conflict, swaggering with self-confidence and entitlement.

Norma, like Medea, is a woman apart, a priestess in a Druid community in Gaul during the period of Roman occupation. She has entered a forbidden relationship with the Roman soldier Pollione, and borne him two children only to learn that he now loves a younger Druid novice, Adalgisa, whom Norma herself had been mentoring. Norma threatens to kill her children who daily remind her of her trespasses, but she loves them so much she cannot go through with it. Ultimately she confesses her sin to the community and accepts a gruesome penalty, death by fire. Pollione, struck by guilt and rekindled love, mounts the pyre with her.

In addition to considerations of plot and character, another factor in Bellini’s compositional process was that he knew the singers who would appear in his opera and wrote music to display their voices, techniques, and artistic personalities. In doing so, he created problems for subsequent generations of performers trained to sing with the techniques and in the styles that would emerge later. Adalgisa should look and sound younger than Norma; yet for most of the last century productions have usually cast a mezzo in this role, although she should be one with a limber voice and easy access to high C. Pollione belonged to the newly emerging class of heroic tenors. Norma herself is an all-encompassing role; Bellini told the first Norma, Giuditta Pasta, that he wrote the role to showcase her “encyclopedic” range of expression.

The music for Norma collapses the usual categories of coloratura, lyric, and dramatic voices – dramatic voices must sing coloratura lines; coloratura and lyric sopranos must sing with dramatic impact. The singer must also act because Norma is such a complex character – that of priestess and leader of her people, mother, friend and mentor, scorned mistress, and noble heroine. She must express spiritual ecstasy, tenderness, bloodthirstiness, all-consuming love, jealousy, furious rage, reminiscence of joys past, authority and vulnerability, scorn and self-sacrifice.

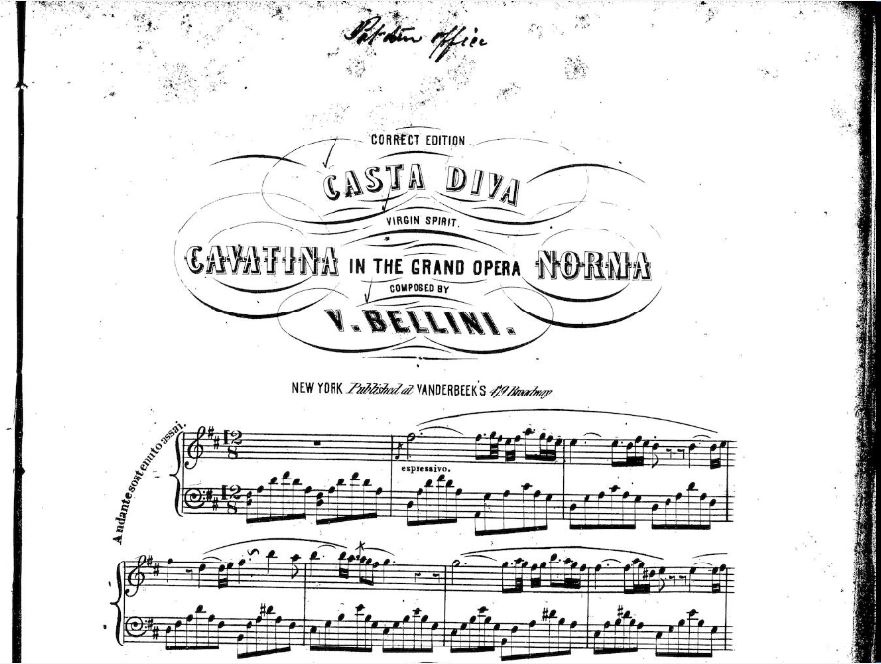

Norma makes her entrance cold with one of the most famous and demanding arias in opera, “Casta Diva.” Two long duets with Adalgisa follow; these require virtuoso command of ensemble singing. The duet with Pollione is most unusual – the two of them are at such cross-purposes they never sing together. In the finale, she must be sublime.

It goes without saying all of this must be communicated through a flawless legato, meaningful diction, and advanced technical skills. In three terrifying pages after Norma realizes that Adalgisa’s suitor is the father of her own children, she twice hurtles with full force through 20- note roulades before vaulting an octave and a half to a sustained high C. Throughout she should display an even scale with plenty of confident power in the lower quarter of her voice, a rich hued middle range, and top notes that vary in dynamics between pianissimo and a flaring fortissimo.

One of today’s leading sopranos sang a few performances of Norma and disarmingly told me once, “I could sing all of it at one time or another, but never in the same performance!” Beverly Sills, who sang Norma for Sarah Caldwell back in 1970s Boston, enjoyed remarking that the role was easy compared to some other parts she had sung. During a notorious Met broadcast intermission feature, the retired Norma, Zinka Milanov. had a different strong opinion and replied to Sills’ assessment, saying “Norma is easy only if you don’t sing it well.”

To perform the title role is a tall order, and it may be one reason the history of this opera has been so spotty. In the first 60 years of opera at The Met, only five sopranos dared to present themselves as Norma: Lehmann, who sang it six times; Rosa Ponselle (29 times) who sang a much-transposed version in lower key, Zinka Milanov (16 times), and Gina Cigna and Maria Callas (both sang it at The Met 6 times).

Norma was, of course, a signature role for Callas, who sang it almost 90 times over her career and recorded it twice in the studio; complete broadcasts or radio fragments of about 10 other performances survive. Her performances at The Met, none of which were broadcast, did not represent a high point for Callas – it is astonishing to re-read the reviews; in them the critics seemed more impressed by the Adalgisa, Fedora Barbieri, than by Maria herself.

Norma was, of course, a signature role for Callas, who sang it almost 90 times over her career and recorded it twice in the studio; complete broadcasts or radio fragments of about 10 other performances survive. Her performances at The Met, none of which were broadcast, did not represent a high point for Callas – it is astonishing to re-read the reviews; in them the critics seemed more impressed by the Adalgisa, Fedora Barbieri, than by Maria herself.

There is no way for anyone today to know what Pasta or Giuliana Grisi, the first Adalgisa and subsequently a great interpreter of Norma, sounded like. In notes for her recording of the opera Cecilia Bartoli makes a case for lighter, more flexible voices than most contemporary listeners are used to. Pasta and Grisi both sang roles now considered better suited to these lighter voices. Critic Conrad L. Osborne, however, has pointed that the opposite position is easily arguable – perhaps the 19th century audiences expected to hear more substantial voices than they now do in operas by Bellini, Donizetti, and early Verdi.

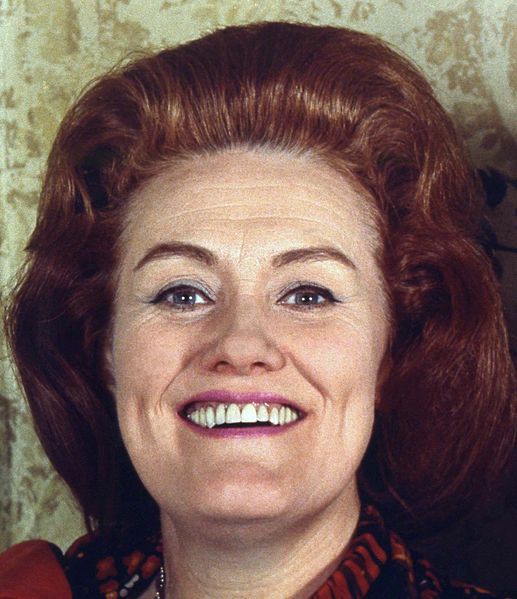

The history of Norma at The Met after 1956 (Callas) illustrates international trends. Callas’ last Norma was The Met’s 63rd (the opera stands at 45th in popularity in The Met’s repertory, according to number of performances); in the proceeding 64 years 105 more performances have been sung by 14 sopranos. Sutherland sang it the most (27 performances); she said all of her other roles were “pieces of cake” compared to this one. She is followed by Renata Scotto (13) Sondra Radvanovsky (12), Montserrat Caballé (11), and Shirley Verrett (10, the first of which was here in the Hynes Auditorium, and no one who was present will ever forget it). Between them Sutherland and Caballé dominated the role for decades around the word; they probably sang it more often than anyone else ever has.

What usually happens is that a Norma excels in one or another aspect of the role while neglecting others – both Sutherland and Caballe were splendid vocalists, for example, but neither was an actress or even a word-oriented singer; Milanov squeaked around some hairpin turns but rose to greatness in the final scenes; colorful Leyla Gencer, the principal Norma in Italy after Callas, was an unconventional and uneven vocalist, but a tremendous performing personality and stage animal.

At least two sopranos have created emergencies for The Met in the last few years by deciding not to sing the role at all after agreeing to perform it: Renee Fleming and Anna Netrebko. To them we owe the performances by Radvanovsky and Angela Meade. A tantalizing might-have-been was the great Norwegian soprano Kirsten Flagstad in the late 1930 – she learned the role at the request of the management but repeatedly and stubbornly declined to perform it.

Of course this list does not include major Normas who did not sing the role at The Met. Among the “coloraturas” were June Anderson, Mariella Devia, and Edita Gruberova who was in her 50s when she sang it for the first time and continued to sing it until the end of last year, in Budapest, when she was 73. Lyric or spinto sopranos who offered Norma with other companies include Lucia Aliberti, Daniela Dessi, Gilda Cruz-Romo and Carol Vaness, who was really excellent. Her Adalgisa in San Francisco was the great Anna Caterina Antonacci who never sang the title role, quipping that there were “about 10 minutes” in her life when she could have done it. Grace Bumbry, like Verrett before her, graduated from Adalgisa to Norma. Another prominent Wagnerian, Gwyneth Jones, organized a performance of Norma on her 60th birthday, wanting to be able to say that she had sung it at least once. She survived honorably – and her birthday party gave an early opportunity to a virtually unknown tenor who sang the cadet role of Flavio, Jonas Kaufmann.

A quick word about other performances of Norma in Boston. BLO offered it with a local cast headed by Anna Gabrieli in the Blackman Auditorium at Northeastern University back in 1982, the early days of the company. And Joanna Porackova sang it with memorable effect in Jordan Hall with Boston Bel Canto Opera. Quincy-born soprano Barbara Quintiliani sang it in Chautauqua, New York a few years ago — and sang it better than some sopranos one has heard at The Met; Quintiliani for years had used phrases from Norma as vocal exercises. So had Mary Curtis-Verna, an admirable soprano from Beverly, Mass. who sang at The Met for a decade between the mid-1950s to closing night of the Old Met in 1966. Curtis-Verna told an interviewer that her late husband, the distinguished voice specialist Ettore Verna, had trained her using phrases from Norma. She was a fearless pinch-hitter who often stepped into leading roles without rehearsal. When this happened to her with Norma, which she sang with Giulietta Simionato at an arena festival in France, she said, “All I had to do was stitch it together – after all, I had been rehearsing it every day since I was a student.”

BLO’s new Norma, Elena Stikhina has been on the international circuit for two or three years, but she has already sung two of Callas’ most iconic roles, Tosca (which she sang for her American debut here in 2017) and Cherubini’s Medea which she sang at the Salzburg Festival last summer. When BLO directors asked her what she would like to sing here next, the Siberian soprano’s response was immediate, unvarying and just one word: Norma.

In the Frame:

A portrait of Bellini circa 1830 no author.

A Norma 1831 premiere poster.

Sketch from Act I Norma Victrolo Book of Opera 1917.

The Casta Diva score. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Maria Callas in 1958 for the talk show Small World CBS.

Joan Sutherland in 1975.

Elena Stikhina in costume as Norma for BLO’s 2020 production. Photo by Sandra Piques Eddy